Chinese Checkers, Halma, Conspirators, Ugolki, Pyramid, and Salta

Written by Howard Fosdick © BestFreeNewGames.com

Overview: In Chinese Checkers, Halma, and several similar games, players take turns in moving their men from one side of the board to the other. The game is race to see who can get all their men across the board first.

What makes it interesting is that you can jump other pieces to move more quickly towards your objective. The fun comes in establishing "jumping chains" and thwarting those of your opponent.

On this page:

Halma

Tips for Play

Similar Games

Which Game is Best?

History of Halma and Chinese Checkers

Photos

Chinese Checkers Rules

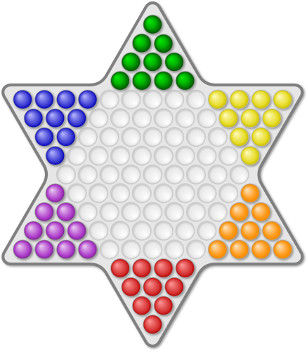

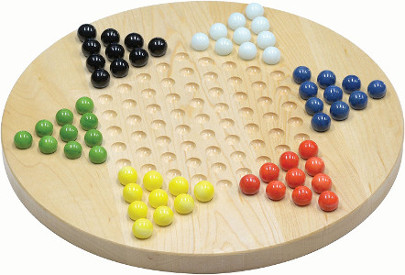

2 to 6 can play Chinese Checkers. When two play, each has 15 pieces. Otherwise each player has 10 men.

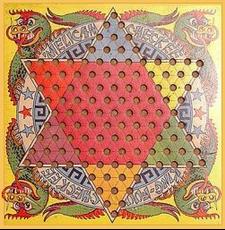

(Click for Printable Image)

The board is a six-pointed star. As the first figure shows, players start by placing their markers into the triangles at the corners of the star. If two play, start your markers across the board from one another.

Four can play as two partnerships, while six can play as either two or three partnerships. Partners sit opposite one another.

Play:

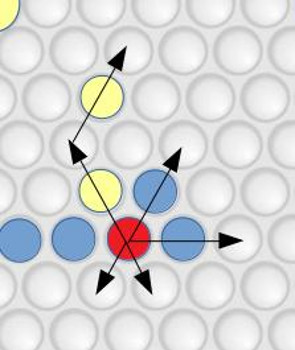

In his turn, a player moves one man to a adjacent vacant position in any direction.

If there is a piece (friendly or enemy) in front of your man -- and there is a vacant position on the other side of that man -- your man can jump over that marker to the vacant position.

Your man may make a string of connected jumps within a single turn. The man may alter direction during a series of jumps.

So jumping is just like in Checkers. The difference is that no men are ever removed from the board. The purpose of jumping is to move your markers more quickly across the board to the winning position. Jumping is not compulsory.

See the second figure for examples of how a man may either move to an adjacent vacant space, jump another marker, or make a "chain jump" over more than one piece.

Winning: First player to move all of his pieces into the starting positions of the opponent sitting opposite wins.

When playing with partnerships, the first parntership to move all their markers into final position wins.

When more than two play individually, it is traditional to continue the game until but one player is left without his markers in the winning position.

Halma Rules

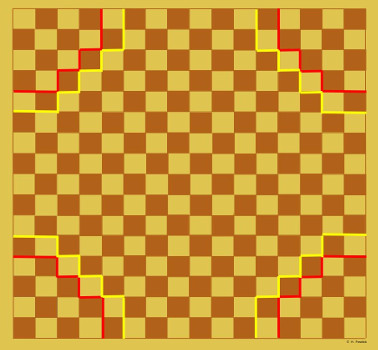

You play Halma with the same rules as Chinese Checkers. The difference is that the board is square and measures 16 by 16 squares.

Either 2 or 4 participants play. If two play, opponents sit opposite each other. Four play individually or in partnerships. When played in teams, partners sit across from one another.

Two players each take 19 markers, and arrange their men in opposite corners of the board. Place them inside the yellow lines.

Four players each take 13 men and position them in one of the four corners of the board, inside the red lines. The figure of the board below shows set-up for both the two- and four- person versions.

Rules for movement, jumping, and winning are exactly the same as in Chinese Checkers.

Variants:

In Halma, two players can control two "armies" each. In Chinese Checkers, two players could control either two or three armies each, or three players could direct two sets of men.

Tips for Play

Just as the rules are the same for Chinese Checkers and Halma, so are the winning strategies.

Obviously, a key goal is to set up your markers for multiple jumps per turn. Remember that you can jump over both your own and enemy pieces. The longer the chain the better, so long as it takes your men in the right direction.

Some players like to "leap-frog" two of their pieces over each other several times. How successful this approach is depends on how hard the opponent tries to defend against it, and how congested the board is where the player tries this.

As in many games, control of the centre of the board is important. What you don't want to have happen is for one of your pieces to become isolated off to the side of the board, and then be forced to plod along one position at a time.

Defense is as important as offense. Moving a marble in position to thwart an enemy chain jump can be as effective as a forward move of one of your own men. It may be preferrable depending on the differentials between movement factors.

The game evolves over time. At first, your goal is to get your men out of their initial positions most efficiently. This probably entails leap-frogging your own pieces and setting them up for some multi-jumps. Then the game matures to where opposing pieces are conflicting and trying to jump over one another in the centre of the board.

Finally, pebbles approach their final landing positions. Here defense of one's starting corner becomes critical. An optimal strategy can make it difficult for your opponent to efficiently occupy the winning territory, or at the least, it can result in the defender launching his final pieces with some meaningful chain jumps.

Play changes a good bit in these two games depending on how many participate. More pebbles on the same size of playing area make for more contention in the centre of the board. It can make it more difficult to set up for chain jumps, as more players take their turns before your next one. With less possibility to coordinate your markers across your turns, the ability to dynamically respond to unanticipated situations and opportunistically capitalize on them becomes more important.

Similar Games: Conspirators, Ugolki, Pyramid, and Salta

Chinese Checkers and Halma are both members of a group of similar games I call Jumping-Race Games. These games share these characteristics:

- To win, you race your men across the board from a set of starting positions to a set of defined end positions.

- Movement is one position at a time

- Single jumps and multiple jumps enable you to accelerate movement. These allow a man to transverse multiple positions in one turn.

- Jumps occur just like in Checkers, but men are never removed from the board. The purpose of jumping is to win the race to the end positions.

- You can jump either your own or enemy pieces.

The Jumping-Race games include: Conspirators, Ugolki, Pyramid, Salta, Halma, and Chinese Checkers.

Conspirators

Conspirators is probably the earliest of the Jumping-Race games. Les Conspirateurs is French and dates to the late 18th century. Some believe it was modelled on the conspiracies so prevalent during the French Revolution.

Conspirators distinguishes itself from other Jumping-Race Games in a couple significant ways:- At the start, players take turns dropping their men into a centre rectangle. So men do not start from fixed positions.

- Instead of moving your markers into the starting positions of your opponent, all men compete to move into the same winning positions located around the edges of the board.

Conspirators is little-known today. Yet it is so different and engaging that we provide a separate webpage devoted to it here.

Ugolki

Another Jumping-Race game is the Russian game called Ugolki. It allegedly dates from about the same period as the Conspirators. Ugolki employs a standard 8 by 8 checkers board. Two players each have 16 pieces that start in opposite corners of the board. See the figure for the initial set-up.

Ugolki follows the same rules as Halma and Chinese Checkers. In fact, given the board shape, it plays just like Halma compressed onto a miniaturised board.

The game ends when either one player occupies the other players' starting positions, or when no moves are possible. In the latter case, the player who has occupied the most squares of his opponent's starting positions wins.

Pyramid

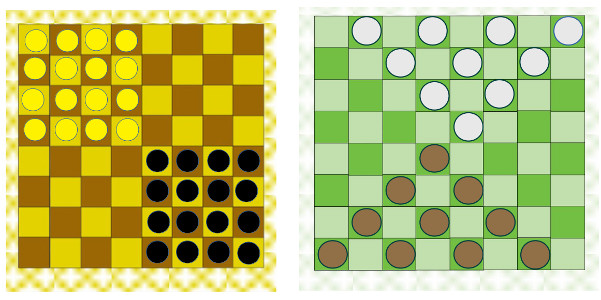

Famous British games historian R.C. Bell describes a game called Pyramid. Like Ugolki, you play it on a standard 8 by 8 checkers board. The games rules are the same as Ugolki, Halma, and Chinese Checkers. Initial positions for the two players are shown in the illustration.

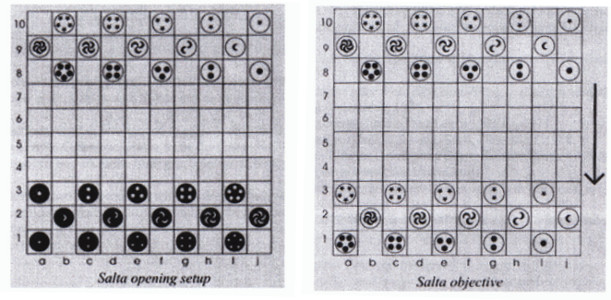

Salta

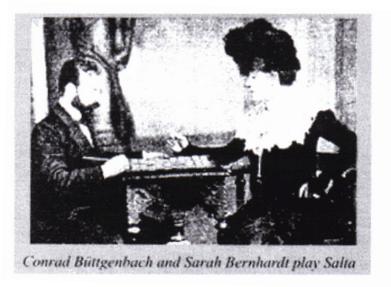

Salta was an important game between 1900 and the first world war. Salta clubs sprang up in Germany, France, and other countries. The game won a Gold Medal at the World Trade Fair in Paris in 1900. (Not surprising, as the board on display contained 5,000 diamonds inlaid into fine mahogany. The playing pieces were made of solid gold.)

German Konrad Heinrich Büttgenbach invented Salta in 1899. He termed it "the humanistic game" because he intended it to be a chess-like game that everyone could play and enjoy.

Ultimately, his creation suffered the same fate as Camelot in the 1930s or Teeko in the 1950s. It was widely popular for over a decade but mainly existed only in game books thereafter. Many believe that the game declined due to the first world war and the subsequent split of its fanbase into Allied and Central Powers antagonists.

Salta plays on a standard, 10 by 10 "continental" checkers board. Pieces are initially positioned as in shown in the left-hand illustration. The big difference from other Jumping-Race games is that each marker is uniquely identified. And, each must be moved into a specific position on the opposite side of the board to win. The goal is to shift all rows of a players' markers seven rows forward. See the right-hand diagram for how this shift operates.

Unlike most Jumping-Race games, jumping is compulsory in Salta. If player fails to make a possible jump, his opponent can force him to recognise it by calling "salta!" Then the player is obligated to take back his last move.

Also, players are not allowed to fully block their opponents from making a move. You can blockade some of your opponent's markers as long as at least one legal move is still available to him. Given that each marker must obtain a specific final board position, blocking can be an effective defensive strategy.

Optional rule: the "120 move" rule ends the game after 120 turns by each player. Each player calculates the total number of moves required to move his unfinished markers into their final destinations -- ignoring any markers in their path to those destinations. Subtract 1 from the player who went first, then calculate the difference between the two players' totals. The winner gets that point difference and the loser gets 0 points. If both players have 0 points, the match is a draw.

We should mention that several prominent sources present incorrect rules for Salta. The rules here are from an original Salta booklet published in 1902 (credited under "Sources" below).

Which Game is Best?

Okay, we've presented rules for all the Jumping-Race games you'll ever hear of. They are five: Chinese Checkers, Halma, Ugolki, Pyramid, and Salta. Which is best?

I believe Chinese Checkers grabs the prize. It's just like Halma but with a more appealing board. And its clever star shape allows any number from two to six to play. Two, three, or six can start from symmetrically opposite corners. In contrast, Halma works best for either two or four players.

Ugolki and Pyramid offer a fun change of pace. But ultimately their main reason for being is that you can play them on a standard checkers or chess board.

Salta became widely popular for a brief period before World War I. It's certainly a more ambitious game in that one must move each piece to a specific location to win. While its fan rating at BoardGameGeek.com is higher than both Chinese Checkers and Halma, I feel the 120 Move Rule exposes its primary weakness. Games can be long. And even then one player often wins on points instead of achieving the game's objective. Salta is challenging but ultimately not a satisfying game for regular play.

History of the "Jumping-Race" Games

As we've mentioned, the earliest Jumping-Race games were Conspirators and Ugolki.

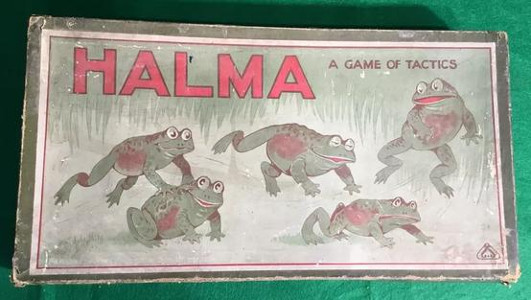

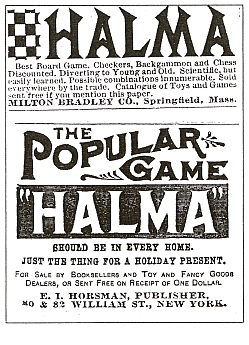

Halma was invented in the early 1880s American physician George Howard Monks. He patented it in 1888. Commercial versions became available about that time and were produced until in the US until the 1960s.

Several internet sources suggest that Dr Monks modelled his creation on an English game called Hoppity, but there's little about "Hoppity" anywhere on the internet other than the mention of the name. In any case, by the time of Halma's invention, Jumping-Race games like Conspirators and Ugolki had been around for a century. So Dr Monks could have gotten the game idea from any of several antecedents.

Chinese Checkers was invented in Germany in 1892 as a Halma variant. It was originally called "Stern-halma", or Star-Halma. In the US, it was introduced under the name "Hop Ching Checkers" by Pressman in 1928. By the 1930s, US sellers changed the moniker to the catchy "Chinese Checkers", and a staple of the boardgame world was born.

Of course, the game's name is misleading. Chinese Checkers is not a form of checkers, nor does it have Chinese origins. Perhaps the sellers were trying to capitalise on the heightened interest in Chinese culture at that time, and the faddish popularity of the game of Mah Jongg in the 1920s and 30s.

In the US, Chinese Checkers has pushed Halma out of the commercial sector. Halma remains popular in Germany and certain other European countries.

Photos

Sources & Credits:

Internet searches turn up many websites that cover Chinese Checkers and Halma. The rules provided here are the most common. One especially thorough website covering these two games is run by Vegard Krog Petersen in Norway, which gets credit for the 1890 Halma ad. Ugolki rules are from Wikipedia here. Salta rules and the board images are from article "Salta: The Humanistic Game", by Ralf Gering, Abstract Games, Issue 8 Winter 2001, accessible via the Wayback Machine here.

The Chinese Checkers board in the first figure appears courtesy of ClipArtKey.com and was donated by Kazunari Utsunomiya, and the board with the black background was donated by Rafa Delannon.

License: Feel free to print, copy, and distribute these rules, so long as you retain this paragraph. Written by Howard Fosdick © 2023, distributed under Creative Commons License BY-ND. HOME